Aboriginal viewpoint:The Mudan Village Incident

In 1664, Zheng Chenggong's

son Zheng Jing ruled over Taiwan. As part of his system of government,

he sent forces ashore at Turtle Cliff Bay to clear the land for

cultivation and establish a military outpost called Tunglingpu.

Gradually, a settlement sprang up around the present-day site of the

Chen-an Temple square in Tungpu Village, Checheng Township.

In 1684, Zheng Jing's son Zheng Keshuang surrendered to the Ching

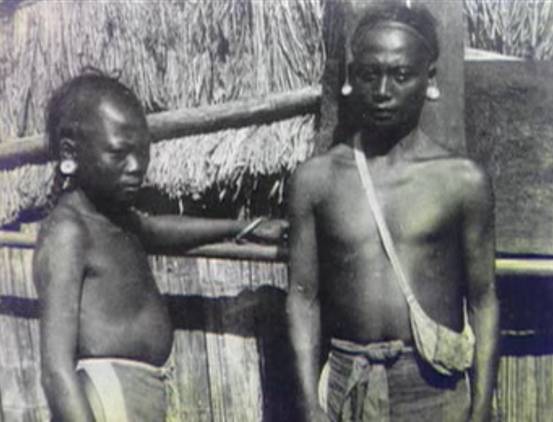

dynasty, which took over governance of Taiwan. At the time, the Paiwan

people were fierce and practiced headhunting. On top of that,

Langchiao's climate was blistering hot in summer and subject to chinook

winds in winter. In just 46 years, eight out of nine assistant

magistrates assigned to the then Fengshan County died of disease. The

county magistrate made an official request to the Ching court to abandon

its jurisdiction over the Hengchun Peninsula.

In 1721, Zhu Yigui of Luohanmen (modern-day Neimen Township in Kaohsiung

County), a duck farmer known as "King Duck," raised an insurrection to

protest government corruption. This event earned the Hengchun Peninsula

a reputation as a hideout for rebels and bandits.

The following year the governor of Fujian Province, Yang Jingsu, ordered

that a stone boundary marker be erected to prohibit any Han Chinese from

moving into Langchiao. The region became an outlying area, a perception

that did not change until the Mutan Village Incident 150 years later.

The incident unfolded in the following way: in 1874, a boat containing a

group of Ryuku Islanders drifted ashore at Langchiao, where they were

killed by local Aboriginals. The Japanese military, which had long had a

greedy eye on Taiwan, used the incident as a pretext for a reprisal

attack. The Japanese came ashore at Sheliao Village in Checheng and,

after defeating the Paiwan of villages such as Mutan and Kaoshihfo, not

only refused to leave but instead made plans to settle in the area for

the long term. Only after British and US mediation did the Ching

government pay reparations for the incident. Realizing Japanese designs

on the region, the imperial envoy Shen Baozhen petitioned the Ching

court to establish a governmental presence at Langchiao, naming the area

Hengchun County and placing it under the jurisdiction of Tainan.

Soon after the Japanese

expeditionary force arrived on Taiwan, it sought to establish military

dominance over the aborigines through a series of aggressive strikes.

Newspaper articles and accounts of the expedition by participants provide

compelling evidence that the fighting proved to be one-sided and short, if

not exactly easy. The fighting began when a group of aborigines ambushed a

small Japanese scouting party on May 18. Using matchlock rifles, they shot

to death two Japanese soldiers and, in their tradition of headhunting, took

the head of one of the Japanese dead before they retreated into the

mountains. Within a few days, Japanese forces mounted a retaliatory strike,

and on May 22 a major battle took place at a ravine that the Japanese

sources called Sekimon (literally, Stone Gate). The Japanese suffered four

killed and twelve wounded, while the aborigines suffered seventy killed and

wounded. In the samurai tradition, Japanese soldiers took the heads of

several of the dead, including the leader of the Butan and his son. A few

days later, Saigo Tsugumichi ordered a major assault on the people of Butan

and Kusakut, the two villages suspected of participating in the slaughter of

the Ryukyuan castaways in 1871, and the assault took place between June 1

and June 3. Following the recommendation of his American military advisers,

Saigo split the Japanese force into three units: the first carried out a

frontal assault against the Butan, the second set out with a Gattling gun in

tow to attack the Kusakut (impassable roads compelled them to send the gun

back to camp before they had traveled far), and the third performed a

flanking maneuver, proceeding north along the coast before heading over the

mountains to attack the Butan from the rear. By the time the fighting ended,

the villages inhabited by the Butan had been burned to the ground, as had

several other villages in the area, and the Butan and Kusakut had been

scattered. By the middle of July, the chiefs of all the aborigine villages

of southern Taiwan had presented themselves at the expeditionary

headquarters and "submitted" to Japanese authority.

Reference

http://www.taiwan-panorama.com/en/show_issue.php?id=200779607061e.txt&table=2&h1=Travel+and+Leisure&h2=In-Depth+Travel

http://www.koreanhistoryproject.org/Ket/C23/E2301.htm

http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/107.2/ah0202000388.html

台灣公共電視:古戰場系列:石門古戰場