Paiwan people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Paiwan)

The brick lower walls of this house show Chinese influence. The two

gables are covered with wooden boards, and the thatched roof is held

down with bamboo strips.

The interior of the house is divided into front and back rooms. The

sleeping platforms are located to the right of the entrance, and a food

preparation area is located to the left. The walls of the back room are

covered with rows of granaries. There are shelves above the hearth. Some

of the houses at Mudan Village are also seen to have stone slab walls

and stone pavement inside and outside the house in the book "An

Illustrated Account of the Taiwanese Aborigines." Further research will

be required to find out whether the materials used is this house are

different due to the tribe's migration.

The Paiwan (排灣) are an aboriginal tribe of Taiwan. They speak the Paiwan

language. In the year 2000 the Paiwan numbered 70,331. This was

approximately 17.7% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them

the third-largest tribal group.

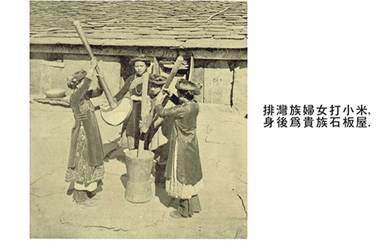

Slabstone House by Paiwan ca. Prior to 1945 |

The unique ceremonies in Paiwan are Masaru and Maleveq. The Masaru is a

ceremony that celebrates the harvest of rice, whereas the Maleveq

commemorates their ancestors or gods.

History

One of the most important figures in Paiwan history was supreme chief

Toketok (ca. 1817 - ca. 1873), who united 18 tribes of Paiwan under his

rule, and in 1867 concluded a formal agreement with Chinese and Western

leaders to ensure the safety of foreign ships landing on their coastal

territories in return for amnesty for Paiwan tribesmen who had killed a

ship's crew on a previous occasion.

Headhunting

The highland tribes were renowned for their skill in headhunting, which

was a symbol of bravery and valor (Hsu 1991:29–36). Almost every tribe

except the Yami (Tao) practiced headhunting. Once the victims had been

dispatched the heads were taken then boiled and left to dry, often

hanging from trees or shelves constructed for the purpose. A party

returning with a head was cause for celebration, as it would bring good

luck. The Bunun people would often take prisoners and inscribe prayers

or messages to their dead on arrows, then shoot their prisoner with the

hope their prayers would be carried to the dead. Han settlers were often

the victims of headhunting raids as they were considered by the

Aborigines to be liars and enemies. A headhunting raid would often

strike at workers in the fields, or employ the ruse of setting a

dwelling alight and then decapitating the inhabitants as they fled the

burning structure.

It was also customary to later raise the victim’s surviving children as full members of the tribe. Often the heads themselves were ceremonially ‘invited’ to join the tribe as members, where they were supposed to watch over the tribe and keep them safe. The indigenous inhabitants of Taiwan accepted the convention and practice of headhunting as one of the calculated risks of tribal life. The last groups to practice headhunting were the Paiwan, Bunun, and Atayal groups (Montgomery-McGovern 1922). Japanese rule ended the practice by 1930, but some elder Taiwanese can recall the practice (Yeh 2003).

Reference

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwanese_aborigines

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paiwan

http://www.flickr.com/photos/abohome/412316891/in/set-72157594572945211/