| Japanese viewpoint |

|

Ryukyu viewpoint |

| Location of Ryukyu Islands |

| The History of Ryukyu |

| Asian trade |

| Japanese invasion |

| Taiwan Expedition of 1874 |

| yang yu wang |

| Ch'ing viewpoint |

| Aboriginal viewpoint |

Japanese invasion (1609)

Around 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi asked the Ryukyu Kingdom to aid in his

campaign to conquer Korea. If successful, Hideyoshi intended to then

move against China. As the Ryukyu kingdom was a tributary state of the

Ming Dynasty, the request was refused. The Tokugawa shogunate that

emerged following Hideyoshi's fall authorized the Shimazu family—feudal

lords of the Satsuma domain (present-day Kagoshima prefecture)—to send

an expeditionary force to conquer the Ryukyus. The occupation of the

Ryukyus occurred fairly quickly, with a minimum of armed resistance, and

King Sho Nei was taken as a prisoner to the Satsuma domain and later to

Edo—modern day Tokyo. When he was released two years later, the Ryukyu

Kingdom regained a degree of autonomy; however, the Satsuma domain did

seize control over some territory of the Ryukyu Kingdom, notably the

Amami-Oshima island group, which was incorporated into the Satsuma

domain.

The Ryukyu Kingdom found itself in a period of "dual subordination" to

Japan and China, wherein Ryukyuan tributary relations were maintained

with both the Tokugawa shogunate and the Ming Chinese court. Since Ming

China prohibited trade with Japan, Satsuma domain, with the blessing of

the Tokugawa bakufu (shogunal government), used the trade relations of

the kingdom to continue to maintain trade relations with China.

Considering that Japan had previously severed ties with most of the

European countries except the Dutch, such trade relations proved

especially crucial to both the Tokugawa bakufu and Satsuma han which

would use its power and influence, gained in this way, to help overthrow

the shogunate in the 1860s.

The Ryukyuan king was a vassal of the Satsuma daimyo, but his land was

not counted as part of any han (fief): up until the formal annexation of

the islands and abolition of the kingdom in 1879, the Ryukyus were not

truly considered part of Japan, and the Ryukyuan people not considered

Japanese. Though technically under the control of Satsuma, Ryukyu was

given a great degree of autonomy, to best serve the interests of the

Satsuma daimyo and those of the shogunate, in trading with China. Ryukyu

was a tributary state of China, and since Japan had no formal diplomatic

relations with China, it was essential that Beijing did not not realize

that Ryukyu was controlled by Japan—if they did, they would end the

trade. Thus, ironically, Satsuma—and the shogunate—was obliged to be

mostly hands-off in terms of not visibly or forcibly occupying Ryukyu or

controlling the policies and laws there. On top of that, in a strange

way, it benefited all three parties involved—the Ryukyu royal

government, the Satsuma daimyo, and the shogunate—to make Ryukyu seem as

much a distinctive and foreign country as possible. Japanese were

prohibited from visiting Ryukyu without shogunal permission, and the

Ryukyuans were forbidden from adopting Japanese names, clothes, or

customs. They were even forbidden from acknowledging their knowledge of

the Japanese language during their t

was

given a great degree of autonomy, to best serve the interests of the

Satsuma daimyo and those of the shogunate, in trading with China. Ryukyu

was a tributary state of China, and since Japan had no formal diplomatic

relations with China, it was essential that Beijing did not not realize

that Ryukyu was controlled by Japan—if they did, they would end the

trade. Thus, ironically, Satsuma—and the shogunate—was obliged to be

mostly hands-off in terms of not visibly or forcibly occupying Ryukyu or

controlling the policies and laws there. On top of that, in a strange

way, it benefited all three parties involved—the Ryukyu royal

government, the Satsuma daimyo, and the shogunate—to make Ryukyu seem as

much a distinctive and foreign country as possible. Japanese were

prohibited from visiting Ryukyu without shogunal permission, and the

Ryukyuans were forbidden from adopting Japanese names, clothes, or

customs. They were even forbidden from acknowledging their knowledge of

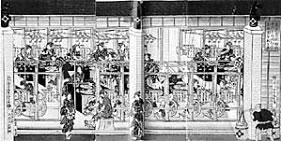

the Japanese language during their t rips to Edo; the Shimazu family,

daimyo of Satsuma, gained great prestige by putting on a show of

parading the King, officials, and other people of Ryukyu to and through

Edo. As the only han to have a king and an entire kingdom as vassals,

Satsuma gained significantly from Ryukyu's exoticness, reinforcing that

it was an entire separate kingdom.

rips to Edo; the Shimazu family,

daimyo of Satsuma, gained great prestige by putting on a show of

parading the King, officials, and other people of Ryukyu to and through

Edo. As the only han to have a king and an entire kingdom as vassals,

Satsuma gained significantly from Ryukyu's exoticness, reinforcing that

it was an entire separate kingdom.

When Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry sailed to Japan to force Japan to

open up trade relations with the United States in the 1850s, he first

stopped in the Ryukyus, as many Western sailors had before him, and

forced the Ryukyu Kingdom to sign Unequal Treaties opening the Ryukyus

up to American trade. From there, he continued on to Edo.

Following the Meiji Restoration, the Meiji Japanese government abolished

the Ryukyu Kingdom, formally annexing the islands to Japan as Okinawa

Prefecture in 1879. The Amami-Oshima island group which had been

integrated into Satsuma domain became a part of Kagoshima prefecture.

King Sho Tai, the last king of the Ryukyus, was moved to Tokyo and was

made a Marquis (see Kazoku), as were many other Japanese aristocrats,

and died there in 1901. Qing China made some diplomatic protests to the

Japanese government, but these proved to have little effect.